CelloFuel™ - Technologies Enabled by Bacterial Contamination Control

We have two active projects using our patented bacterial contamination control technology:

Making affordable and healthy protein (TorulaFeed™) from rice, corn, and wheat

Potential market size: $300 Billion per year for animal feed, potential large market for human nutrition. Main countries for producing TorulaFeed are USA, China, Russia, India - because large amounts of low-cost grain, low-cost energy for steam, low-cost urea.

Status: Patent granted in Russia, submitted in USA, China, India. Engineering design complete, 3D model and drawings in progress, construction of 1/2 size pilot fermenter starting in January 2026 in the UK, pilot plant operations in June 2026.Improving efficiency and profitability of Brazilian and Indian sugarcane ethanol plants

Potential market size: $10 Million per year cost savings per Brazilian sugarcane ethanol plant, 350 plants, $3.5 Billion per year cost savings in Brazil, $200 Million per year in India.

Status: Patent granted in Brazil, submitted in India. Marketing of project in Brazil and India started.

(Cellofuel™, TorulaFeed™ and TorulaBurger™ are trademarks of Hamrick Engineering.)

What is TorulaFeed?

Torula yeast (Candida utilis) has been used for more than a century to feed fish, animals and people.

TorulaFeed is made from ground grain (rice, corn or wheat) and urea (for nitrogen in protein) using fermentation.

About 70% of the grain is starch, and this starch is hydrolyzed to sugar (maltose) using enzymes. This sugar is used to grow Torula yeast to make a 50% protein product (TorulaFeed) for fish, animals and people.

The valuable part of grain is the 10% protein it contains, and this protein is incorporated into TorulaFeed.

The less valuable parts of grain are fiber (arabinoxylan) and oils (Omega-6) and these are used along with sugar to grow the Torula yeast.

TorulaFeed is cost-competitive with soybean meal but much healthier.

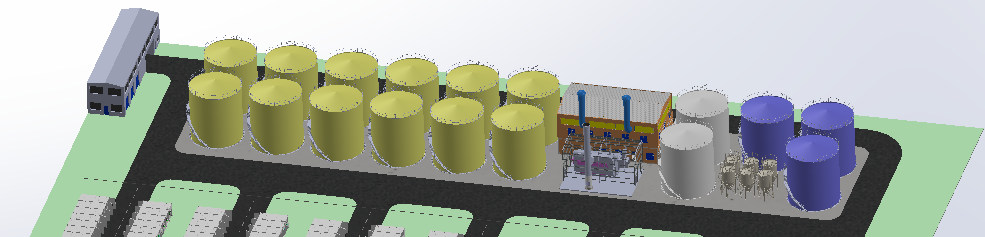

TorulaFeed Plant Processing 400,000 MT Grain per Year

A large US bioethanol plant can process 400,000 metric tons of corn per year at a capital cost of $88M. This is an example of a TorulaFeed plant processing this same amount of grain, at a capital cost of $14M and producing 260,000 metric tons of TorulaFeed per year.

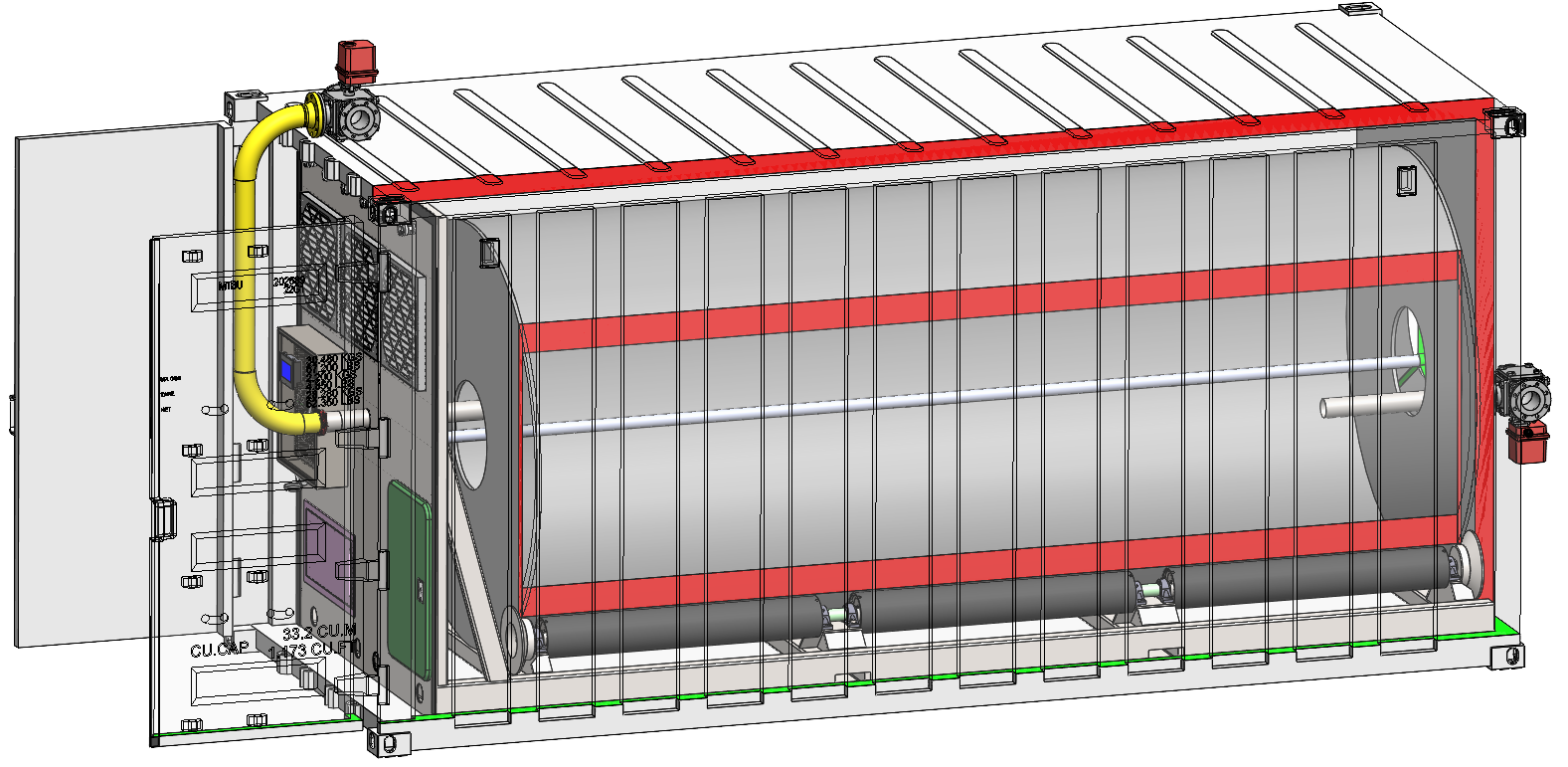

It’s made up of 700 20-ft shipping containers, each containing a 1.5 m x 5 m rolling drum bioreactor. Grain is stored in grain silos (yellow) is hammer-milled (in the building next to the grain silos) and the flour is stored in flour silos (white). Flour is loaded into each shipping container with pneumatic conveying, each container converts 0.85 MT of flour to 0.55 MT of TorulaFeed every 12 hours, the TorulaFeed is deactivated and dried in each container, and the resulting TorulaFeed is pneumatically conveyed to product silos (orange) and packaged and loaded in trucks for shipment. There is no waste water.

Water tanks (blue) feed a water main along the road next to the silos and branch off to each train of 50 containers. Similarly, enzyme solutions, urea solutions, and yeast nutrition solutions are distributed by a main and branches. Steam is generated next to the hammer mill and is similarly distributed - a main line along the road and branches to each container. Power is similarly distributed to the containers. Each container uses a 3-way ball valve to pump liquids from each branch.

The roads between trains of 50 containers are for heavy maintenance of the drums, which are skid mounted. Moist, humid air is pulled from the back of each container and rises upwards. Cooler, dryer air is pulled from the entrance of each container, through air filters in each container and through the tumbling fermenting cake inside the drum, which is cooled through evaporation by this air flow.

There is no risk in scaling up this plant, since once the performance of a single container is proven, the remainder of the plant is made up of well-understood technologies from building bioethanol plants.

Most of the manufacturing work will be in factories building containers in different countries and should significantly reduce the time to build a plant. The optimal locations for these plants are near where the grain is grown. The market in the US, India, China and Russia are at least 100 plants in each country.

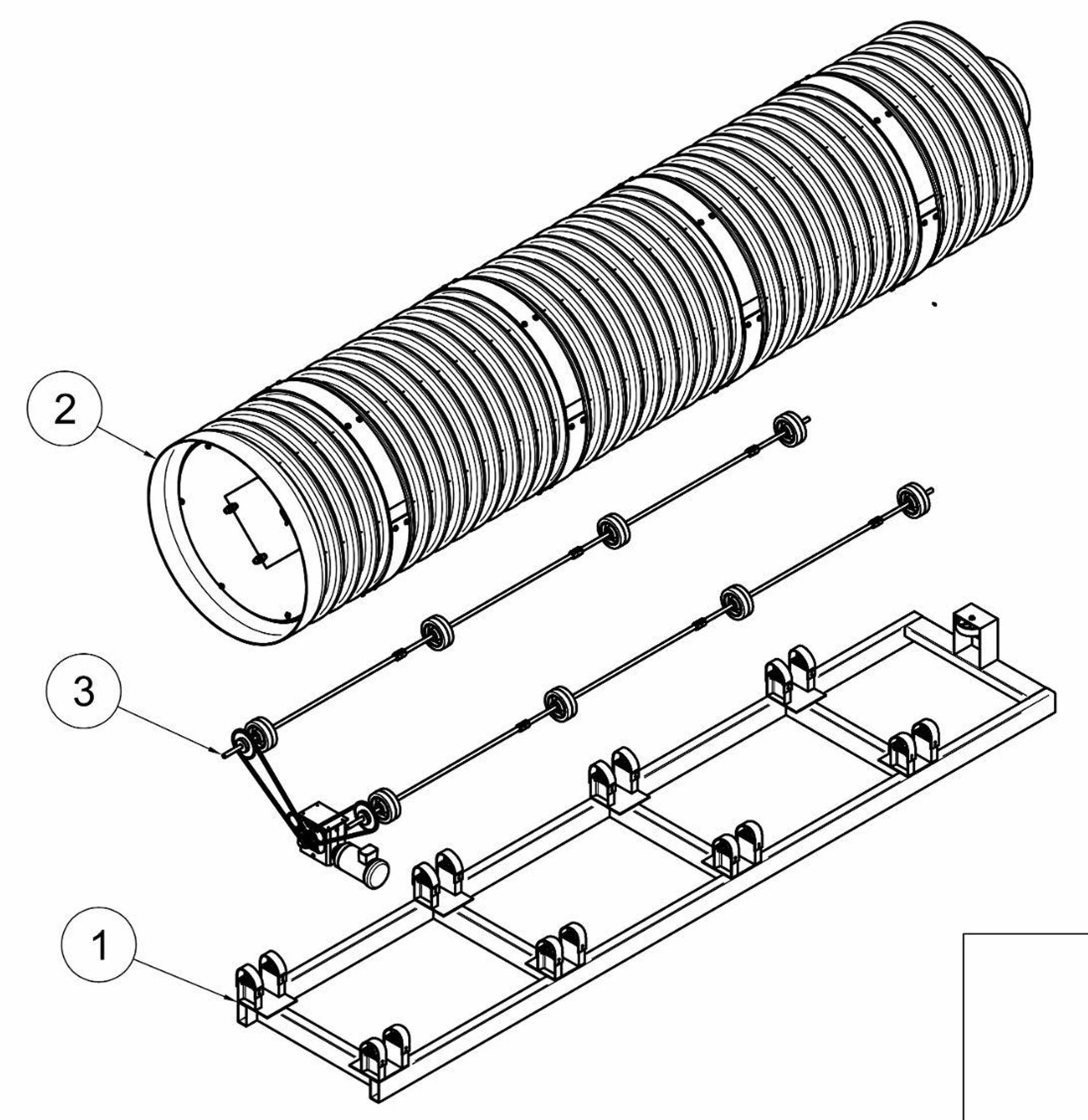

TorulaFeed Container Details

Each TorulaFeed container is made up of a 20-ft shipping container containing a 1.5 m x 5 m rolling drum bioreactor. The drum is a double-wall corrugated (DWC) HDPE drum, with a smooth interior and a corrugated exterior. The central axis contains a DN50 stainless steel pipe for distributing liquids and steam. The drum contains 4 lifters 4.5 m long (not shown). The drum rotates at 10 rpm for 12 hours during the following processing steps:

Water, enzymes and yeast nutrition are added and mixed

Flour is pneumatically conveyed into the drum and well-mixed at room temperature, water activity 0.95 (moisture 36% wb)

Steam added to raise the temperature to 70°C for 30 minutes to sterilize and partially gelatinize the flour

Temperature is gradually dropped to 35°C while hydrolyzing the amylose leached from the flour

Recycled yeast is obtained with a peristaltic pump from partner container (12 hour cycle difference)

Rapid fermentation for 6 hours, evaporative cooling to keep temperature at 35°C

Recycled yeast is transferred with a peristaltic pump to partner container

Grow for 2 hours with reduced urea and phosphorus to reduce RNA and glycogen content

Deactivation of Candida utilis and sterilization of TorulaFeed with steam

Drying with steam-heated air and evaporative cooling, (moisture 13% wb)

Extraction of TorulaFeed with pneumatic conveying

Note that these containers run unattended for months at a time, are self-cleaning, there is no waste water, about 1200 kg of sanitary steam is needed every 12 hours and is recycled, and about 2 kW of power is needed to rotate the drum at 10 rpm and run the fan at 8000 m3/h. Communication is by WiFi to a central maintenance station.

| Cost saving elements | Impact | Prerequisite |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-state fermentation with rolling drum | No centrifuge or spray dryer, low power, no foam, high oxygen transfer | |

| Partial gelatinization at 70°C | No jet cooker, enables faster enzymatic hydrolysis at 35°C | |

| Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) | Faster production of yeast | |

| Evaporative cooling | No plate heat exchanger or water chiller | Bacterial contamination control |

| Corrugated HDPE rolling drum | 1/10 cost of stainless steel | Evaporative cooling |

| Composite low-cost rollers | 1/10 cost of standard rollers | |

| Vibrator mounted on each lifter | Faster production of yeast from thin layer slumping | |

| Yeast recycling | Faster production of yeast | Bacterial contamination control |

| Growing Torula yeast | Uses the oil and arabinoxylan in rice, corn, and wheat to produce protein | |

| Sterilizing after each cycle | Raises temperature to 80°C with 100% humidity | |

| Low-cost enzymes | Sunson Enzymes are high quality and low-cost | |

| Continuous Clean-In-Place | Uses sterilization and abrasion for CIP | |

| Containerized | Mass production, easy installation |

Enzymes used to make TorulaFeed

Sunson maltogenic amylase, 0.1 - 1 kg/Ton of flour, 20-80°C

for hydrolyzing amylose in starch to maltose

Sunson pullulanase, 1-2L/Ton of flour, 40-65°C

for hydrolyzing amylopectin in starch to amylose

Sunson xylanase, 5-10 g/Ton of flour, 30-70°C

for hydrolyzing fiber (arabinoxylan) in grain to xylose and arabinose

Sunson Nutrizyme PHY (phytase), 100 g/Ton, 30-85°C

for hydrolyzing phytic acid and producing free inorganic phosphate and minerals

For wheat:

Sunson Acid Protease APRS, 0.01-0.5 kg/Ton, 30-70°C

for hydrolyzing gluten-forming proteins to peptides without producing free amino nitrogen

These enzymes have significant activity at pH 4-6. These enzymes have also significant activity during simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) at 35°C and are not denatured during partial starch gelatinization at 70°C

Rolling Drum Bioreactor Clean-in-Place (CIP)

At the beginning of every fermentation cycle, the hammer-milled grain is treated with steam injection with 100% relative humidity. This kills all bacteria, yeast, and fungi from the grain.

When growing Candida utilis in a rolling drum bioreactor using the non-starch parts of rice, corn, and wheat (i.e. bran) for support, the particulate nature of moistened bran, combined with the drum's rotation at 10 rpm and the presence of 8 lifters (150 mm high), promotes constant tumbling and cascading of the substrate. This mechanical action generates abrasion between the bran particles and the drum walls, which are made of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) - a smooth, non-stick material with low surface energy that inherently resists adhesion.

Abrasion from the tumbling substrate effectively scours the drum interior, preventing the accumulation of material on the walls. Literature on RDBs for SSF (including with wheat bran) emphasizes challenges like heat transfer, mixing, and contamination but does not report wall fouling or biofilm thickening as issues, even in long-term operations.

Candida utilis primarily grows on the bran particles rather than forming extensive biofilms on the drum surfaces, especially under the dryish, aerated conditions with evaporative cooling and pneumatic conveying. The continuous addition and removal of bran further maintains dynamic flow, reducing opportunities for static buildup.

Thus, the abrasion of the bran keeps the drum clean over multi-month periods, with no evidence of progressive biofilm formation.

In addition, we use steam injection to inactivate, sterilize and dry TorulaFeed, so it can be packaged for shipment directly from the rolling drum bioreactor. We do this by raising the temperature of the TorulaFeed to 80°C with 100% relative humidity, without the steam impinging on the HDPE in the drum. This completely inactivates the yeast and any bacteria that might be in the TorulaFeed. We then use evaporative cooling to prepare the TorulaFeed for packaging and sale.

Contamination Control

Bacterial contamination is the top challenge in industrial-scale ethanol fermentation or yeast growth. Our patented method prevents it by using urea as the sole nitrogen source and keeping nickel below 1 mg/kg—eliminating acid washes or antibiotics. Urea is added gradually during simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF), accelerating the process without issues. It works at pH 4-7.

PCT Patent WO2024092285A2

U.S. Patent No. 12,297,423

U.S. Patent App. No. 19/202,827, filed May 8, 2025

Rotating Drum Bioreactor

Our RDB fermenter leverages our contamination control patents for year-round aerobic yeast growth on hammer-milled rice, corn, and wheat. Its core is a double wall corrugated HDPE rolling drum, enabling large, containerized fermenters at less than $1,000/m³—vs. more than $15,000/m³ for traditional ones (e.g., corrugated HDPE rolling drum costs less than $1,000 vs. more than $9,000 for stainless steel). Operating costs are lower than submerged fermentation.

It uses maltogenic amylase with pullulanase with partial gelatinization at 70°C, SSF at 35°C with Torula yeast (also known as Candida utilis and Cyberlindnera jadinii), and yeast/enzyme recycling for speed.

Evaporative cooling skips heat exchangers, cutting CAPEX/OPEX and cleaning needs. Drums self-clean via abrasion during rotation. No foam is formed during fermentation. Drying is cheap at ~50% moisture in the slurry. Units are containerized and automated.

Healthier than Soy Protein

Our RDB fermenter yields yeast that's healthier than soy protein and competitively priced. Soy farming relies on harmful herbicides/pesticides that enter the food chain, plus soy has anti-nutritional compounds (e.g., trypsin inhibitors, lectins). Yeast offers better amino acid balance, sustainability (less land needed), and nutrition for fish/chicken.

Our low CAPEX and OPEX make TorulaFeed a cost-effective and nutritious alternative to soy meal.

Yeast from Rice, Corn, and Wheat

Our RDB fermenter cost-effectively produces protein-rich yeast from hammer-milled rice, corn, and wheat. Starch is hydrolyzed to maltose using 70°C partial gelatinization, then using maltogenic amylase and pullulanase with yeast grown simultaneously (SSF). This is the cheapest aerobic sugar source—mirroring POET's ethanol process but aerobic for yeast. Drying energy is low at ~50% moisture.

Torula yeast is Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS), approved globally for consumption by fish, animals, and people, is widely sold by Lallemand as a flavor enhancer, and has been safely used since the 1930s for fish, animal, and human consumption.

We increase the amount of Torula yeast in TorulaFeed by adding xylanase enzymes to produce arabinose and xylose from arabinoxylan (fiber) in wheat and corn, which Torula yeast metabolizes. Torula yeast also metabolizes the oil in rice, corn, and wheat, thus reducing the linoleic acid (omega-6) content of TorulaFeed.

TorulaFeed Technical Details

Overview

Recently, many companies in the plant-based meat replacement market have struggled with falling revenues. What’s causing these issues? The primary factors are nutritional controversies surrounding plant-based foods and their higher prices - they often cost significantly more than animal-based proteins.

Parallel to the plant-based meat replacement market is a much larger opportunity: protein sources for fish and animal feed that are healthier than soy meal. Yet soy meal remains the least expensive protein option in animal feed.

TorulaFeed addresses both markets. This innovative blend of Torula yeast and grain protein delivers high-quality nutrition at a lower cost. It's less expensive, more digestible, and more nutritious than soy meal or other plant- and animal-based proteins.

Yeast defies traditional categories: it's neither plant- nor animal-based, yet healthier than both, and suitable for fish, animals, and humans (including vegans). After all, most people consume yeast daily in bread. Not only is it nutritious and safe, but we've also solved its biggest hurdle - producing yeast protein more affordably than plant- or animal-based alternatives - through breakthroughs in cost-effective manufacturing.

Emerging research underscores why this matters: protein supports your health, while excessive carbs and seed oils (rich in omega-6 fatty acids) can harm your health. Grains like rice, corn, and wheat typically contain just 10% protein, alongside 70% carbs (mostly starch), 1–4% arabinoxylan (a type of fiber), and 0.5–3% omega-6 oils. Our proprietary technologies efficiently recover the protein from these grains while converting the less healthy components (starch, arabinoxylan, and omega-6 oils) into Torula yeast.

Potential Market Size for TorulaFeed Protein

TorulaFeed protein competes in the plant-based meat replacement market, valued at between $20-24 billion with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7-9%.

TorulaFeed protein also competes in the animal feed protein ingredients market, valued at around $230-250 billion in 2023-2024 and projected to reach $410 billion by 2032 at a CAGR of 6-9%, fueled by animal feed and aquaculture expansion.

Specifically for aquaculture (a key target due to TorulaFeed's fish-friendly profile), the global aquafeed market stands at $67-72 billion in 2024-2025, expected to grow to $100-112 billion by 2030-2032 at a CAGR of 4-7.5%.

Balanced protein

Protein is more valuable when the constituent amino acids are a balanced source of food for fish, animals, and people. Rice, corn, wheat and bran protein is deficient in lysine and rich in methionine while yeast protein is rich in lysine and deficient in methionine. A mixture of these two types of protein is therefore more balanced (and thus more valuable) than rice, corn, wheat and bran protein alone. This balance is the reason for the modern trend of vegan meals made from seitan (vital wheat gluten) mixed with nutritional yeast.

Improved healthiness

Our mission is to produce TorulaFeed that is less expensive and healthier than protein from legumes such as soybeans, peas, and faba beans. These legumes contain many anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) that make them less than ideal for animal feed and human nutrition. These include trypsin inhibitors, lectins, oligosaccharides, phytic acid, saponins, antigens, isoflavones, tannins - all of which are harmful in feed. Carnivorous fish (salmonids/shrimp) suffer enteritis/growth issues at more than 30% soy. Young animals (piglets/chicks/calves) face digestive problems; poultry suffer from diarrhea and reduced growth. TorulaFeed has no ANFs, yielding healthier fish/chicken/pigs and healthier plant-based protein for people.

Reducing cost

The high cost of producing yeast protein compared to soybean protein is one of the main reasons it hasn’t previously been used as a replacement for soybean protein, so we’ve focused on patented technologies to make low-cost production possible.

Our process reduces capital expenses (CAPEX) and operating expenses (OPEX). We use enzymes to convert the starch and xylan in ground rice, corn, wheat and bran into maltose, xylose, and arabinose while simultaneously growing Torula yeast (Candida utilis) on these sugars in a rotating drum bioreactor (RDB). Air blown through the drum enables evaporative cooling, and we add water to maintain moisture without excess wetness. We harvest partial yeast batches, recycling the remainder along with enzymes to speed up subsequent cycles.

Depending on the country, rice, corn, wheat and bran are the least expensive sources of starch-derived sugars, yielding not just single-cell protein (SCP) but also converting oil to protein and incorporating the grain's protein, potassium, and phosphorus into the feed.

System design

Our portable design fits in 20-ft shipping containers, using Double Wall Corrugated (DWC) High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) rolling drums that are 1.5 m in diameter, and 5 m long. These drums are made from food-grade HDPE and don’t leach nickel like stainless steel does. These containers are factory-assembled, transportable by truck/train, and support rapid large-scale setup.

Capacity and cost of production

The rolling drum has a volume of 8.8 m3. It can be filled to 1/3 of this volume, which can hold 0.85 metric tons (MT) of ground grain and 1.7 MT of water. The rolling drum produces about 0.55 MT of TorulaFeed in a 12 hour cycle. A single container processes 620 MT/y of grain and produces 401 MT/y of TorulaFeed.

A site with 100 containers can process 62,000 MT/y of grain and produce 40,100 MT/y of TorulaFeed. A TorulaFeed site with 700 containers can process as much grain as a large US corn ethanol plant, with a capital cost of $14M and a yearly profit of $36 M. The capital cost of the same size US corn ethanol plant is about $88 M, about 6 times more expensive than a TorulaFeed plant.

Assuming $200/MT for grain, $20/MT for urea, $20/MT for enzymes, $20/MT for inactivation and drying, and 2 kW of power to rotate the drum and power the fans, the production cost of TorulaFeed is about $369/MT.

The modern measure of protein quality is the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). The DIAAS score of soybean meal is about 90 and the DIAAS score of TorulaFeed is about 120.

The world market price for soybean meal is about $350/MT. Since TorulaFeed has a 30% higher DIAAS score than soybean meal, has fewer Anti-Nutritional Factors (ANFs), and is more nutritious, TorulaFeed can be sold profitably at a price above $500/MT with a profit margin above 30%. The payback period is less than 6 months.

Assuming the capital cost of a single container is $10,000, a single container can make a profit of (500-369) * 401 = $52,531/y. Assuming a $1 M investment in 100 containers and another $1 M investment in grain handling, hammer milling, flour bins, yeast nutrition tanks, and pneumatic conveying equipment, a $2 M capital investment can make a profit of $5.1 M/y.

Technologies

This process is made possible by using our bacterial contamination control technique. This allows solid-state fermentation in an RDB with yeast/enzyme recycling and evaporative cooling - avoiding expensive submerged fermenters, heat exchangers, centrifuges, and dryers.

We focus on cost-effective SCP technologies for feed healthier than soy. We're licensing patents, tech, and designs to clients with cheap rice, corn, and wheat and access to feed markets, targeting the USA, Brazil, Russia, India, China, Argentina, and Mexico. Contact us for licensing information at info@cellofuel.com.

Our core patent blocks bacterial growth by limiting nickel (less than 1 mg/kg) and using urea as the sole nitrogen source - yeast thrives without nickel, but bacteria cannot. Use of this patent enables evaporative cooling and yeast recycling.

Process control

For optimal growth of Torula yeast, the temperature of the substrate in the rolling drum needs to be maintained in an optimal range. The amount of cooling available is limited by the humidity of the air, so we control the temperature of the substrate by varying two parameters - the amount of air blown through the drum (evaporative cooling) and the rotation rate of the drum (oxygenation).

A key part of the process control is a proprietary technique for varying growth conditions to produce Candida utilis with reduced levels of ribonucleic acid (RNA) and glycogen (a carbohydrate similar to starch).

We provide the process control software as part of licensing. The main input is the temperature of the slurry every meter inside the drum, using Bluetooth-LE sensors between the outer wall and inner wall, powered by RF scavenging.

Our baseline process cycle time is 12 hours, comprising about 8 hours for fermentation and another 4 hours for pneumatic loading, starch hydrolysis, yeast inactivation, product drying and unloading. This short fermentation time is made possible by yeast recycling.

Taste

Rice, corn, wheat and bran protein has a relatively mild flavor and Torula yeast provides an intense umami (meaty) flavor, giving the mixture a meaty flavor which is very tasty to fish, animals, and people.

Sample recipes

We’ve produced some recipes using TorulaFeed to show how to use it to produce healthy and tasty hamburgers with a perfect balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. TorulaFeed can also be used in other recipes for meatballs and ground beef. Food manufacturers can produce TorulaBurger patties for sale using similar recipes, preprepared for cooking.

Composition of TorulaFeed

Protein quality

The protein-enriched dried mixture that we produce, TorulaFeed, has about 50% protein with a high DIAAS score for protein quality of about 116 to 123. Torula yeast and grain protein have both been used for decades to replace soy in fish and animal feed, and the protein-rich mixture of these is well suited to replace soy. Soy, pea, and faba bean protein are also commonly used in foods as meat replacements, but TorulaFeed has fewer anti-nutritional factors (ANF’s).

Torula yeast has twice as much lysine as grain protein and grain protein has twice as much methionine as Torula yeast, so together they have a well-balanced amino acid composition. There’s no significant benefit to supplementing TorulaFeed with either lysine or methionine.

The most modern measure of protein quality is the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). See below for DIAAS values for TorulaFeed from brown rice, corn, and wheat.

Vitamins

Torula yeast is enriched in all B vitamins except for vitamin B12, including thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin. Torula yeast is also enriched in ergosterol, which can be converted to vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) via UV irradiation.

Fatty acids

TorulaFeed contains very low levels of fatty acids, because Torula yeast metabolizes oils in rice, corn, wheat and bran to protein. Figure 3 in Babij (1969) shows that as the glucose is depleted and the Torula yeast enters the stationary state, the amount of fatty acids within the Torula yeast is very low.

Because our process converts the oil from rice, corn, and wheat to protein before high-temperature drying, because there are very low levels of fatty acids in the Torula yeast to oxidize, and because Torula yeast contains significant trehalose (antioxidant), there are no rancid odors from drying or storing TorulaFeed. Since the shelf life of inactivated, dried Torula yeast is 1-2 years, TorulaFeed also has a shelf life of 1-2 years.

We produce both animal feed and hamburger patties with TorulaFeed by adding an 80/20% mixture of canola oil and flaxseed oil to enrich TorulaFeed with equal amounts of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids.

Because canola oil also contains tocopherol anti-oxidants (Vitamin E), the omega-3 fatty acids from flaxseed oil aren’t oxidized when this oil is used for frying or baking, making it an ideal oil to incorporate in hamburger patties with a perfect balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. This oil also tastes good. A 1:1 mixture of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids is also well suited for fish, chicken and pig feed nutrition.

| Feed | DIAAS Score | Protein / 100 g feed | Linoleic acid (LA) / 100 g feed | Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) / 100 g feed | LA : ALA ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown rice | 89 | 8.5 g | 0.90 g | 0.04 g | 22.5 |

| Yellow dent corn | 62 | 8.8 g | 2.12 g | .05 g | 42.4 |

| Wheat | 60 | 14.8 g | 0.67 g | .07 g | 9.6 |

| Faba beans | 55 | 26 g | 0.58 g | 0.05 g | 11.6 |

| Pea protein concentrate | 82 | 80 g | 1.69 g | 0.32 g | 5.3 |

| Soybean meal | 91 | 49 g | 0.82 g | 0.11 g | 7.5 |

| Torula yeast | 95 | 50 g | 0.5 g | 0.125 g | 4 |

| TorulaFeed (Rice) | 116 | 54 g | .25 g | 0.0625 g | 4 |

| TorulaFeed (Corn) | 123 | 56 g | .25 g | 0.0625 g | 4 |

| TorulaFeed (Wheat) | 116 | 54 g | .25 g | 0.0625 g | 4 |

| Food | DIAAS Score | Protein / 100 g food | Linoleic acid (LA) / 100 g food | Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) / 100 g food | LA : ALA ratio |

| Atlantic salmon (wild) | 100 | 20 g | 0.17 g | 0.14 g | 1.2 |

| Atlantic salmon (farmed) | 100 | 20 g | 1.67 g | 0.11 g | 15 |

| Chicken (pasture raised) | 108 | 21 g | 1.50 g | 0.15 g | 10 |

| Chicken (grain fed) | 108 | 21 g | 2.20 g | 0.05 g | 44 |

| Eggs (pasture raised) | 112 | 13 g | 1.00 g | 0.15 g | 6.7 |

| Eggs (grain fed) | 112 | 13 g | 1.83 g | 0.06 g | 30.5 |

| Pork (grain fed) | 113 | 21 g | 0.50 g | 0.02 g | 25 |

| Beef (grass fed) | 109 | 21 g | 0.20 g | 0.08 g | 2.5 |

| Beef (grain fed) | 109 | 21 g | 0.40 g | 0.02 g | 20 |

| Milk (grass fed) | 114 | 3.3 g | 0.08 g | 0.05 g | 1.6 |

| Milk (grain fed) | 114 | 3.3 g | 0.10 g | 0.02 g | 5 |

TorulaFeed in Fish and Animal Feed and in Food

Palatability (taste) of TorulaFeed

Grain protein and bran protein has very little free glutamic acid and is relatively tasteless.

Dried Torula yeast is rich in glutamic acid, giving this mixture a palatable, meaty taste, while still being suitable for vegetarians and vegans.

Color of TorulaFeed

Grain protein from rice and wheat is a neutral color, while grain protein from corn is yellowish because it contains carotenoids.

These carotenoids can be a problem in aquaculture, particularly for salmonid species like rainbow trout and salmon. High inclusion levels in fish diets have been linked to suboptimal muscle pigmentation, where yellow carotenoids deposit in the flesh, resulting in an undesirable yellowish tint rather than the preferred pink or orange hue from added astaxanthin. For non-salmonid fish (e.g., catfish or tilapia), similar yellowing of fillets can occur.

When fed to poultry, these carotenoids are often valued for enhancing the yellow coloration of egg yolks and skin, which is desirable in many markets.

No significant drawbacks related to carotenoids are noted when consumed by animals or people, and they often provide antioxidant and eye-health benefits.

Dried Torula yeast is a tan or light brown color and does not contribute significant color when consumed by fish, animals or people.

RNA content of Torula yeast

People require about 0.8 g of protein per day per kg of body weight. The average person weighs about 62 kg (137 lbs) and thus requires about 50 g of protein per day. If half of the daily protein requirements are supplied by TorulaFeed, this would require 25 g of protein from TorulaFeed - about 61 g of TorulaFeed per day, of which would be about 34 g of Candida utilis yeast per day. Under normal growth conditions, the ribonucleic acid (RNA) content of Candida utilis is about 10% of dry matter, so 34g of Candida utilis contains about 3.4 g RNA. The recommended maximum daily consumption of RNA is less than 2 g/day, so it’s necessary to reduce the RNA content of Candida utilis for fish, animal, and human consumption.

We have a proprietary method for reducing the RNA and glycogen content of Candida utilis by varying the growth conditions. This reduces the average daily consumption of RNA to well below 1 g/day while simultaneously reducing the glycogen content.

High-temperature drying of TorulaFeed serves dual purposes: inactivating the yeast cells to render them non-viable and safe for consumption, while also enhancing digestibility by breaking down tough cell wall components. TorulaFeed has low levels of lipids (fats) so high-temperature drying doesn’t produce any rancid flavors from the oil in rice, corn, and wheat. The lack of lipids in TorulaFeed also makes it possible to store TorulaFeed in dry form for long periods (fats can go rancid from oxygen). It is also enriched in B vitamins. We produce both animal feed and hamburger patties with TorulaFeed by adding an 80/20% mixture of canola oil and flaxseed oil to enrich TorulaFeed with equal amounts of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids.

Because canola oil contains tocopherol anti-oxidants (Vitamin E), the omega-3 fatty acids from flaxseed oil aren’t oxidized when this oil is used for frying or baking, making it an ideal oil to incorporate in hamburger patties with a perfect balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids. This oil also tastes good. A 1:1 mixture of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids is also well suited for fish, chicken and pig feed nutrition.

Health aspects of TorulaFeed when consumed by fish, animals and people

TorulaFeed is healthy for fish, chicken, pigs, and people. Feed conversion ratios (kg feed/kg weight gain) are 1.0-2.0 for fish, 1.7-2.0 for chicken, 2.5-3.5 for pigs, and 6.0-10.0 for cattle (least efficient). Torula yeast's feed value dates to 1940s Germany. Global production: ~140M tons poultry, 110M tons pigs, 90M tons aquaculture yearly.

Essential fatty acids

People can't produce these fatty acids and without them people can’t live:

Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA, omega-3): Heart/brain health, anti-inflammation (in flaxseeds, chia, walnuts).

Linoleic Acid (LA, omega-6): Skin/hair, growth, membranes (in vegetable oils, nuts).

There are metabolic disorders caused by consuming an excess of omega-6 fatty acids, and TorulaFeed, along with an 80/20% mixture of canola oil and flaxseed oil, produces a feed that has equal amounts of ALA and LA. The human body converts them to EPA/DHA and a balance of ALA and LA in the diet prevents inflammation caused by too much LA.

Soybeans, peas, and faba beans have an omega-6 excess and no omega-3/EPA/DHA, leading to poor health when consumed by people, either directly or indirectly. Yeast is healthier to consume.

Anti-Nutritional Factors (ANFs) in legumes

Legumes such as soybeans, peas, and faba beans, contain many anti-nutritional factors that make them less than ideal for feeding to fish, animals, and people. These include trypsin inhibitors, lectins, oligosaccharides, phytic acid, saponins, antigens, isoflavones, tannins - all of which are harmful in feed. Carnivorous fish (salmonids/shrimp) suffer enteritis/growth issues at more than 30% soy. Young animals (piglets/chicks/calves) face digestive problems; poultry suffer from diarrhea and reduced growth. Yeast has no ANFs, yielding healthier fish/chicken/pigs.

Enhancing digestibility of TorulaFeed

There are no ANFs in yeast and grain residuals, but phytate and the non-starch polysaccharide (NSP) arabinoxylan can reduce the digestibility of TorulaFeed.

Grains contain phytate, which binds phosphate and causes chelation of many critical minerals. Even though Candida utilis secretes phytase to free the phosphate in phytate, some supplementation with phytase during growth of TorulaFeed may be helpful.

Arabinoxylan from grain is indigestible by fish, chickens, pigs, and people. Even though Candida utilis secretes xylanase, some supplementation with xylanase during fermentation may increase the yield of Candida utilis (which grows on xylose and arabinose) and improve the digestibility of TorulaFeed.

| Animal | Recommended Inclusion Level of TorulaFeed | Key Basis for Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 20% (up to 25% in some trials) | No adverse growth or health effects; potential gut benefits; higher may disrupt microbiome in mixed diets. |

| Chicken | 20% | Maintains performance and carcass yield; higher worsens feed efficiency. |

| Pig | 20-26% | No negative growth or diarrhea; improves efficiency; up to 40% protein replacement. |

| Dog | Up to 20% | High palatability and digestibility, anti-inflammatory benefits; no regulatory limit, but aligned with studies. |

| Cat | 20% | High palatability and digestibility; limited by fecal quality concerns. |

Using TorulaFeed in Food

TorulaFeed is a dried mixture of the processed rice, corn, and wheat solids and Torula yeast that tastes like meat. It doesn’t require refrigeration and can be rapidly reconstituted as a healthy hamburger meat (ground beef) replacement. It is well suited to any market with health-conscious, vegetarian, and vegan consumers. It is tasty, with a nutty, smoky, or umami flavor profile derived from the yeast, combined with the milder, grain-like taste of the rice, corn, and wheat residues. Torula yeast is well-established as a flavor enhancer in foods, where it is valued for its savory qualities and ability to improve overall palatability in various products. It is suitable for inclusion in foods, because both ground grain and Torula yeast are recognized as safe for consumption (with Torula yeast holding GRAS status from the FDA), and because similar yeast-based single-cell protein products or fermented substrates are already incorporated into items like seasonings, spreads, soups, sauces, snacks, and vegetarian alternatives.

TorulaFeed has no dietary carbs, has a good balance of essential amino acids and is low-fat (no lipids), making it an especially healthy addition to our diet.

TorulaFeed is produced with reduced ribonucleic acid (RNA) content, which solves problems with elevated uric acid levels from high nucleic acid content. The process described uses food-grade enzymes and a yeast strain extensively utilized in the food industry, supporting its suitability.

Recipes Using TorulaFeed for Vegan Burgers

Common elements in all recipes

The oil is an 80/20% mixture of canola oil and flaxseed oil, optionally supplemented with flavors such as truffle.

The binder is either E461 methylcellulose or ground flaxseed. If ground flaxseed, add an equal amount of canola oil.

The addition of canola oil makes a 1:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids, and adds antioxidants.

Basic low-carb vegan burger recipe

This straightforward recipe emphasizes TorulaFeed flavor with a binder for a firm texture. It's minimally seasoned to highlight the umami from the Torula yeast, keeping net carbs low. Yields 4 patties (about 100g each after cooking).

Ingredients:

200g TorulaFeed

15g binder; absorbs moisture

5g mixed spices (e.g., onion powder, garlic powder, smoked paprika)

2g salt

150-180ml water (adjust for consistency)

10g oil (for mixing or cooking; adds minimal carbs)

Instructions:

Mix the TorulaFeed, binder, spices, and salt in a bowl.

Gradually incorporate water and oil, stirring until a cohesive dough forms (let sit 10-15 minutes to gel and bind).

Divide into 4 portions and shape into patties.

Pan-fry in a non-stick skillet over medium heat for 4-5 minutes per side until crispy or bake at 190°C (375°F) for 15-20 minutes.

Serve with low-carb toppings like sliced tomatoes or vegan cheese.

Nutritional Notes:

About 19.6g protein per patty

No net carbs per patty

About 1g omega-6 and 1g omega-3 fatty acids per patty

Spinach-infused low-carb vegan burger recipe

This variation adds finely chopped spinach for added moisture and nutrients, binder without eggs or grains. It maintains a low-carb count with a fresh, green flavor profile. Yields 4 patties.

Ingredients:

200g TorulaFeed

100g fresh spinach (chopped and wilted to reduce volume)

12g binder

5g herbs and spices (e.g., basil, cumin, black pepper)

2g salt

120ml water

8g oil (for wilting spinach and binding)

Instructions:

Wilt chopped spinach in 4g oil over medium heat for 2-3 minutes, then cool.

Combine TorulaFeed, binder, herbs, spices, and salt.

Mix in wilted spinach, water, and remaining oil; rest 10 minutes for binding.

Form 4 patties and grill or pan-fry for 5 minutes per side.

Enjoy on a bed of greens for an ultra-low-carb meal.

Eggplant and spice low-carb vegan burger recipe

Incorporating roasted eggplant for a smoky, meaty texture, this formula uses the binder to make a firm patty, resulting in ~8g net carbs per patty. The eggplant adds volume without significant protein or carbs. Yields 4 patties.

Ingredients:

200g TorulaFeed

80g eggplant (diced and roasted)

14g binder

6g spices (e.g., chili powder, coriander, turmeric)

2g salt

140ml water

10g oil (for roasting and mixing)

Instructions:

Dice eggplant, toss with 5g oil, and roast at 200°C (400°F) for 15 minutes until soft.

Mash roasted eggplant slightly and mix with TorulaFeed, binder, spices, and salt.

Add water and remaining oil; let mixture hydrate for 15 minutes.

Shape into 4 patties and bake at 190°C (375°F) for 20 minutes, flipping once, or pan-fry.

Pair with pickled veggies for added tang.

Using E461 methylcellulose as a binder

The market leaders in vegan meat patties are Impossible Burger, Beyond Burger, Gardein Ultimate Plant-Based Burger, Lightlife Plant-Based Burger, and Incogmeato Burger Patties. All use E461 methylcellulose as a binder in their plant-based burger patties, which produces a juicier, meat-like texture that some people prefer. This firms up when heated, helping patties hold shape during cooking and offering a juicy bite when cooled. Methylcellulose is derived from plant-based cellulose fiber, is approved for food use worldwide and is relatively inexpensive.

Using flaxseed as a binder

Ground flaxseed, when combined with equal amounts of canola oil, also makes a healthy binder. It’s not quite as firm when cooking, but some consumers feel it’s more natural than methylcellulose, that it adds equal amounts of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids and that it is quite tasty. When combined with canola oil’s antioxidants, it doesn’t produce off-flavors from peroxidation when frying.

Cost of protein in foods

When comparing the cost per kg of protein of different foods, commercially available vegan meat patties are 3 times more expensive than ground beef and are almost 50 times more expensive than TorulaBurger (see below). Vegan meat patties are marketed to wealthy consumers who aren’t price-sensitive to the cost of food, while TorulaBurger is a low-cost source of protein as healthy as salmon, but at 1/30 the price per kg of protein in salmon.

| Protein source | Retail cost per kg protein |

|---|---|

| Impossible Burger Patty | $157/kg |

| Beyond Burger Patty | $124/kg |

| Salmon Fillet (Atlantic, farmed) | $85/kg |

| Ground Beef (85-90% lean) | $51/kg |

| Eggs | $48/kg |

| Pork Loin (boneless, skin) | $31/kg |

| Chicken Breast (boneless, skinless) | $30/kg |

| TorulaBurger | $3/kg |

Target Markets

We target regions with abundant cheap rice, corn, and wheat and with strong demand for fish and animal feed. Sugars from hydrolyzed rice, corn, and wheat are cheaper than molasses for growing yeast.

India has the least expensive white rice, in the form of 100% broken rice (a byproduct of milling). About 20 MMT/y is produced and costs about $250/MT in the internal Indian market. Adding rice bran at about $200/MT can make a product similar to brown rice, but less expensively since broken rice is much less costly than white rice.

| Country | Corn | Price | Wheat | Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 377 MMT/y | $157/MT | 54 MMT/y | $221/MT |

| China | 295 MMT/y | $321/MT | 140 MMT/y | $285/MT |

| Brazil | 132 MMT/y | $191/MT | 8 MMT/y | $231/MT |

| Argentina | 50 MMT/y | $174/MT | 19 MMT/y | $232/MT |

| Russia+Ukraine | 41 MMT/y | $175/MT | 105 MMT/y | $234/MT |

| India | 43 MMT/y | $315/MT | 113 MMT/y | $293/MT |

| Mexico | 25 MMT/y | $210/MT | 3 MMT/y | $262/MT |

Improved Contamination Control in Brazilian Sugarcane Ethanol Plants

We have developed technologies for cost-effective control of bacterial contamination during large-scale yeast fermentation (both aerobic and anaerobic). Instead of adding anti-bacterial substances to a fermenter or using sulfuric acid washes to kill bacteria during yeast recycling, we eliminate nickel leaching and use urea as the sole nitrogen source. Bacteria can’t grow on urea without nickel as a co-factor, but yeasts only need biotin to grow on urea.

This technique allows fermentation without requiring aseptic conditions and is thus much less expensive than traditional fermentation techniques.

Example use in Brazil:

This technique can be used in sugarcane ethanol plants in Brazil to improve efficiency, produce more ethanol, reduce foaming and reduce the strong odor from the vinasse. The changes using this contamination control technique enable using yeast recycling without acid washing to speed up fermentation time in flex plants.

Changes required: Minimal changes are needed to integrate our contamination control technique:

Use urea as the only nitrogen source, replacing ammonium sulfate

Use fed-batch feeding of urea

Make sure heat exchangers use stainless steel grade 316 (not grade 304)

Don’t use acid wash, recycle yeast cream directly from centrifuge

Clean vats with high pressure water spray, without caustic

Benefits:

Reduces wild yeast contamination: Without bacterial contamination, contamination by D. bruxellensis and other wild yeasts doesn’t occur when using a fast-growing S. cerevisiae strain like PE-2.

Reduces foaming: Foaming is reduced because the extracellular protein from Lactobacillus is eliminated.

Reduces strong odors: Eliminating sulfur from the wash and changing ammonium sulfate to urea results in significant reduction of sulfur in the vinasse, which reduces the strong odor from bacteria producing hydrogen sulfide from the vinasse. Not using sulfur dioxide in sugarcane juice clarification can further reduce the strong odor from the vinasse.

Reduces distillation column fouling: Eliminating the sulfuric acid wash eliminates adding soluble calcium sulfate to the distillation columns when recovering ethanol from this wash. Calcium sulfate from the wash also precipitates in the distillation column, causing fouling and requiring more cleaning.

Improves distillation efficiency: Sulfuric acid wash water dilutes the mash being distilled, which increases the energy and time needed for distillation. It’s more efficient to carry this ethanol with the recycled yeast into the next fermentation cycle.

Increases profits: The cost savings are considerable due to reducing the time per batch by 2-4 hours and improving process efficiency. The increase in income for a typical Brazilian sugarcane ethanol plant producing 6% more ethanol (12 million liters) due to eliminating bacterial contamination in fermenters is approximately $6,000,000 per year, assuming an ethanol price of $0.50 per liter. This figure could range from $3.6 million to $8.4 million depending on ethanol prices or plant size. The cost savings from eliminating the sulfuric acid wash is about $500,000 per year. The cost savings from eliminating calcium sulfate from the distillation columns is about $1.3 million per year. The cost savings from reducing the batch cycle time from 12-15 hours to 10-12 hours is about $1.3 million per year. The total cost savings are about $10,000,000 per year for a large sugarcane ethanol plant.

The Fermentation Cycle in Brazilian Sugarcane Ethanol Production

In Brazil, sugarcane ethanol production typically employs the Melle-Boinot process, a fed-batch fermentation process, which is widely used due to its efficiency and scalability. The process begins with the preparation of a substrate, usually sugarcane juice or molasses, derived from sugarcane processing. This substrate, rich in fermentable sugars like sucrose, glucose, and fructose, is fed into large fermentation vats. The fermentation is carried out by the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a robust strain well-suited for ethanol production.

Fermentation Phase: The yeast ferments the sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide over a period typically ranging from 6 to 12 hours, depending on factors like temperature (maintained around 30–34°C), sugar concentration, and yeast activity. The process is "fed-batch," meaning the substrate is added incrementally to avoid overwhelming the yeast with high sugar levels, which could inhibit fermentation.

Harvesting Phase: Once fermentation is complete, the fermented broth (containing ethanol, yeast, water, and residual sugars) is centrifuged. This separates the liquid fraction (called "wine," containing ethanol) from the yeast biomass. The ethanol-rich liquid proceeds to distillation to purify and concentrate the ethanol, while the yeast is collected for reuse.

Yeast Recycling: In the standard process, approximately 90–95% of the centrifuged yeast is recycled to the next fermentation cycle to maintain high productivity and reduce costs. Before recycling, the yeast is often subjected to an acid wash (using sulfuric acid) or a water wash to remove contaminants, particularly bacteria, and to refresh the yeast by reducing the buildup of fermentation byproducts and dead cells.

Vat Cleaning: After each cycle, the fermentation vats are cleaned to remove residues and prevent contamination in the next batch. This cleaning typically involves caustic soda (sodium hydroxide), often heated, to ensure thorough sanitation, followed by rinsing.

This cycle repeats multiple times, leveraging the recycled yeast to maximize efficiency in Brazil’s large-scale ethanol industry, which produces billions of liters annually.

Improvements with No Bacterial Contamination and No Yeast Washing

Now, let’s consider a modified process where no bacterial contamination occurs during fermentation, and no acid or water wash is applied to the centrifuged yeast. Instead, 95% of the yeast is recycled directly without washing. Here’s how this alters and potentially improves the process:

Operational Improvements

Elimination of Ethanol Recovery from Acid Wash:

In the standard process, acid washing the yeast can dilute any residual ethanol clinging to the yeast biomass. This ethanol must be recovered (e.g., via distillation), adding an energy-intensive step. By skipping the wash, no ethanol is lost to a wash solution, eliminating this recovery process and saving energy.

No Acid Neutralization:

Acid washing requires neutralizing the acidic yeast slurry (e.g., with a base like lime) before recycling to avoid harming the yeast or altering the fermentation pH. Skipping the wash eliminates the need for neutralization, reducing chemical inputs, waste treatment, and associated costs.

Simplified Process:

Removing the washing step streamlines operations by reducing the number of unit processes, lowering labor, equipment maintenance, and water usage.

These changes enhance plant efficiency by cutting energy, chemical, and operational expenses.

Equilibrium Concentration of Metabolites and Dead Cells

Without washing, the recycled yeast carries over fermentation metabolites (e.g., organic acids like acetic acid, glycerol, and higher alcohols) and weak or dead yeast cells into each new cycle. Here’s how this stabilizes:

Accumulation: Initially, the concentrations of these components increase with each cycle as 95% of the yeast, including its metabolites and dead cells, is reused.

Removal and Dilution:

5% Yeast Loss: The 5% of yeast not recycled (discarded or lost) removes a small fraction of these components from the system.

Fresh Substrate Addition: Each cycle introduces fresh sugarcane juice or molasses, diluting the metabolite concentration in the fermentation broth.

Equilibrium: Over multiple cycles, an equilibrium concentration is reached where the rate of metabolite production and dead cell accumulation equals their removal (via the 5% yeast loss) and dilution (via fresh substrate). This equilibrium level would be higher than in a washed-yeast system, where washing removes some metabolites and dead cells each cycle. However, since Saccharomyces cerevisiae is tolerant to many of its own byproducts (up to certain thresholds), and no bacterial competition exists, this higher concentration is manageable without significantly impairing fermentation efficiency.

Quantitatively, this equilibrium depends on fermentation conditions (e.g., sugar concentration, cycle duration), but qualitatively, it stabilizes at a level reflecting the balance of production, loss, and dilution.

Cycle Time Improvement with Water-Washed Vats

Finally, consider how not washing the yeast improves the overall cycle time when fermentation vats are cleaned with water instead of caustic:

Standard Cycle Time Components:

Fermentation: 6–12 hours.

Harvesting (centrifugation): ~1–2 hours.

Yeast Washing: In the standard process, acid or water washing, neutralization, and rinsing add 1–2 hours (depending on scale and method).

Vat Cleaning: Caustic cleaning, often heated and followed by rinsing, takes 2–3 hours or more.

Modified Process:

No Yeast Washing: Eliminating the washing step saves 1–2 hours per cycle. After centrifugation, the yeast is immediately recycled, cutting a significant preparation step.

Water-Washed Vats: Cleaning vats with water instead of caustic is faster—potentially reducing cleaning time to 1–2 hours—since it avoids heating, prolonged chemical exposure, and extensive rinsing. Water suffices here because bacterial contamination is absent, and the goal is simply to remove physical residues (yeast, sugars) rather than sanitize deeply.

Combined Effect: Without yeast washing, the time between fermentation cycles shrinks directly. Pairing this with quicker water-based vat cleaning further shortens the downtime, allowing cycles to restart sooner. For example, a cycle that took 12–15 hours (fermentation + harvesting + washing + caustic cleaning) could drop to 10–12 hours, boosting throughput.

The absence of bacterial contamination enables these simplifications without risking fermentation performance, as bacteria—typically controlled by acid washing and caustic cleaning—are not a factor.

Conclusion

In Brazilian sugarcane ethanol production, the standard fed-batch fermentation cycle involves fermenting sugarcane juice or molasses with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, followed by centrifugation, yeast washing, and vat cleaning with caustic. When no bacterial contamination occurs and 95% of the centrifuged yeast is recycled without washing:

Plant operations improve by eliminating ethanol recovery and acid neutralization, saving energy, chemicals, and time.

Metabolite and dead cell concentrations reach a higher but stable equilibrium, balanced by yeast loss and substrate dilution, tolerable due to no bacterial interference.

Cycle time shortens by removing the yeast washing step (1–2 hours saved) and, when vats are water-washed instead of caustic-cleaned, further reducing cleaning time (1–2 hours vs. 2–3+ hours), enhancing overall efficiency.

This optimized process leverages the absence of contamination to simplify and accelerate ethanol production.

Reduces fermentation time:

In the improved process, fermentation time is reduced because the yeast is no longer subjected to the stress of acid washing. Here’s how this works:

Acid Washing in Traditional Processes

In traditional ethanol production, yeast is often recycled between fermentation cycles to maximize efficiency. To control bacterial contamination during this recycling, the yeast is washed with sulfuric acid. However, this acid exposure stresses the yeast cells. The stress can damage their cell membranes, lower their viability, and slow their metabolic activity. When these stressed yeast cells are reused, they need time to recover before they can ferment sugars efficiently. This recovery period, or lag phase, extends the overall fermentation time.

Eliminating Acid Washing in the Improved Process

In the improved process, the acid washing step is skipped entirely. After fermentation, 95% of the yeast is separated using centrifugation and directly reused in the next cycle without being exposed to acid. Since there’s no acid wash, the yeast avoids this stress. As a result:

Higher Viability: The yeast cells remain healthier, with intact membranes and better metabolic function.

No Recovery Time: Without the need to recover from acid stress, the yeast can start fermenting the new batch of sugarcane juice or molasses immediately.

How This Reduces Fermentation Time

The key to shorter fermentation time lies in the yeast’s improved condition:

Faster Start: In the traditional process, acid-washed yeast may enter a lag phase as it recovers from stress, delaying the start of active fermentation. In the improved process, this lag phase is minimized or eliminated because the yeast is unstressed and ready to work right away.

More Efficient Fermentation: Healthier yeast converts sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide more quickly. Without the burden of repairing acid-induced damage, the yeast ferments at a faster rate, completing the cycle sooner.

How Much Time Is Saved?

The exact reduction in fermentation time depends on factors like the yeast strain, sugar concentration, and fermentation conditions. However, by avoiding acid stress, fermentation could be shortened by approximately 10–20%. For a typical 8–12 hour fermentation cycle, this might mean a savings of 1–2 hours per batch.

Additional Advantages

Beyond reducing fermentation time, skipping acid washing simplifies the process. It eliminates the need for acid, neutralizing agents, and extra steps like treating the wash, which also saves time and resources. With faster fermentation cycles, the plant can process more batches in the same timeframe, increasing overall productivity.

Conclusion

By eliminating acid washing, the improved process keeps the yeast healthier and more active, avoiding the stress that slows fermentation in the traditional method. This leads to a quicker start and more efficient sugar conversion, ultimately reducing the fermentation time while improving the process’s simplicity and efficiency.

Who are we?

Hamrick Engineering was founded in 2013 by Edward B. Hamrick.

Edward (Ed) Hamrick graduated with honors from the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) with a degree in Engineering and Applied Science. He worked for three years at NASA/JPL on the International Ultraviolet Explorer and Voyager projects and worked for ten years at Boeing as a Senior Systems Engineer and Engineering Manager. Subsequently, Ed worked for five years at Convex Computer Corporation as a Systems Engineer and Systems Engineering Manager. Ed has been a successful entrepreneur for the past 25 years.

Alex Ablaev, MBA, PhD is Sr. Worldwide Business Developer. Alex previously worked for Genencor's enzymatic hydrolysis division, and is the President of the Russian Biofuels Association as well as General Manager of NanoTaiga, a company in Russia using CelloFuel technologies in Russia.

Alan Pryce, CEng is Chief Engineer. Alan is an experienced professional mechanical engineer - Chartered Engineer (CEng) – Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) - with 10+ years’ experience in the mechanical design and project management of factory automation projects in UK and European factories. He has been a Senior Design Consultant and project manager for over 30 years working for Frazer-Nash Consultancy Ltd involved with many design and build contracts in the military, rail, manufacturing, and nuclear industries.

Maria Kharina, PhD, is Sr. Microbiology Scientist. Maria has a PhD in Biotechnology and is a researcher with 10+ years of experience. Maria was a Fulbright Scholar in the USA from 2016-2017.

Beverley Nash is Director of Marketing. Beverley has run Nash Marketing for over 30 years and has extensive experience in marketing planning and development for both new and established businesses. Beverley has worked for many global corporations in the technical marketplace and has been responsible for both the planning and management of many programs dealing with all aspects of company and product growth.

Dr. Ryan P. O'Connor (www.oconnor-company.com) provides intellectual property strategy consulting and patent prosecution. Dr. O'Connor holds a degree in Chemical Engineering from University of Notre Dame and a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from University of Minnesota. He has filed more than 1000 U.S. and PCT applications and is admitted to the Patent Bar, United States Patent & Trademark Office.

Hamrick Engineering Patent Portfolio

Contamination control when growing yeasts

U.S. Patent No. 12,297,423 status: Granted

International Patent App. No. PCT/US2023/083031 status: Published

CN118043470A (China) status: Published

RU2826104 (Russia) status: Granted

BR112024003499 (Brazil) status: Granted

Contamination control when growing yeasts - Continuation-In-Part

US Patent App. No. 19/202,827 status: Filed May 8, 2025

Methods for fermenting carbohydrate-rich crops

US9499839 (USA) status: Granted

RU2642296 (Russia) status: Granted

BR112016005352 (Brazil) status: Granted

CN107109440B (China) status: Granted

EP3140411 (European Union) status: Granted

AR106148A1 (Argentina) status: Granted

IN328228 (India) status: Granted

Notified of grant by Ukraine patent office

Method for fermenting stalks of the Poaceae family

US9631209 (USA) status: Granted

RU2650870 (Russia) status: Granted

EP3277825B1 (EU) status: Granted

MX363750B (Mexico) status: Granted

CN107849585B (China) status: Granted

BR112017008075 (Brazil) status: Granted

Methods and apparatus for separating ethanol from fermented biomass

US10087411 (USA) status: Granted

RU2685209 (Russia) status: Granted

EP3541489A1 (EU) status: Granted

MX371710 (Mexico) status: Granted

BR112018075838A2 (Brazil) status: Granted

IN332722 (India) status: Granted

CA3025016A1 (Canada) status: Granted

UA119630C2 (Ukraine) status: Granted

Methods and systems for producing sugars from carbohydrate-rich substrates

US9194012 (USA) status: Granted

RU9194012 (Russia) status: Granted

CA2884907 (Canada) status: Granted

CN105283468 (China) status: Granted

EP3004178 (European Union) status: Granted